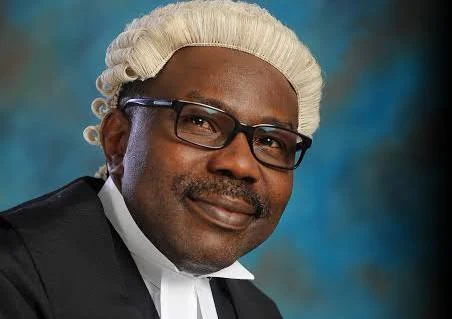

The vanishing culture of caring for elders – Dr. Muiz Banire

Every society is ultimately judged by how it treats its most vulnerable members, the children, the poor, and the elderly. In traditional African settings, old age was a crown of honor; the elders were the moral compass, custodians of wisdom, and pillars of the family unit. In Nigeria, respect for elders was deeply woven into the social fabric, upheld by family structures and reinforced by cultural and religious values. The Yoruba say, Agba kii wa loja, ki ori omo tuntun wo—“When elders are present in the market, the child’s head cannot go crooked.”

This implies that in our culture, the elderly were the compass of wisdom, the embodiment of grace, and the archive of our communal heritage. They were not just old people; they were living libraries, repositories of moral and historical consciousness. Sadly, that culture of reverence and care is fast fading in Nigeria. Today, the same elders who once toiled to raise children, communities, and nations are left to languish in neglect and poverty. The old order of compassion and duty is giving way to an age of selfishness and forgetfulness. We are, quite literally, losing our humanity. Yet, the Nigeria of today tells a different story.

With urbanization, migration, economic hardship, and the gradual erosion of communal living, the care for seniors has become increasingly neglected. Many elderly citizens now live in despair, loneliness, and economic deprivation, without the comfort of family or the support of the state. The once-sacred responsibility of caring for one’s parents and elders has been displaced by the pressures of modernity and survival.

Gone were therefore the days when the aged were treasured. In the Nigeria of old, to grow grey hair was a badge of honour. The extended family system ensured that no elder walked alone. Every child, nephew, cousin or neighbour saw it as a duty, indeed, a moral debt, to care for the aged. An elderly person’s hut was never empty; food was shared, chores were done for them, and their opinions were sought before any major decision. In Yoruba land, the saying “Iya ni wura, Baba ni jigi” (Mother is gold, Father is a mirror) captured the sanctity of parental figures. The Igbo had their Ndi Ichie, whose counsel guided kings and clans. Among the Hausa, elders were revered as Magada, guardians of ancestral wisdom. Every culture recognized that the elders were not merely old; they were indispensable.

Thus, historically, the Nigerian social order revolved around the extended family system, where the aged were the repository of ancestral knowledge and experience. In every compound, the oldest member presided over family meetings, resolved disputes, and mediated between the living and the ancestors.

Elders were revered, consulted, and never abandoned. Their welfare was a shared family duty, and their opinions carried the weight of collective conscience. In those days, there were no old people’s homes because every home was, in fact, a home for the old. No one thought of “institutional care” because communal care was the foundation of society itself. The philosophy was simple: today’s child will become tomorrow’s elder. In Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa communities alike, the elderly were not left to fend for themselves.

The communal system ensured that even the poorest among them were fed, housed, and cared for. Old age was not viewed as a burden but as a reward for a life of service. But as Nigeria evolved into a more individualistic, urbanized, and cash-driven society, this deeply humane tradition began to erode.

Fast-forward to modern Nigeria, and one beholds a painful irony. The elders who once gave their best to society now face their sunset years in uncertainty. They are left behind in villages, while their children pursue survival in cities or abroad. In urban centres, many seniors are confined to their rooms, trapped between high medication costs and emotional isolation. The collapse of the extended family system, worsened by urbanization, migration, and harsh economic realities, has left a generation of aged Nigerians stranded. Some now resort to begging in markets, mosques and church premises.

Others rely on charity from neighbours or faith-based organizations. The situation is particularly dire for those who worked in the informal sector without pensions or savings. Nigeria’s pension system only covers a small fraction of the elderly population, mostly former public servants and formal sector workers. Even those fortunate to have worked in the Civil Service often spend their last years chasing unpaid pensions, victims of a cruel bureaucracy and corruption that treats their labour as disposable.

In rural communities, many seniors are left behind as their children migrate to cities or abroad. The old parents wait endlessly for remittances that sometimes never come. Urban seniors, on the other hand, face isolation, confined within apartments, forgotten by society, and burdened by the high cost of healthcare.

What a tragedy that men and women who built our institutions and taught our children are now reduced to waiting endlessly for what is rightfully theirs. Our healthcare system compounds their plight. With almost no geriatric facilities and limited access to affordable drugs, many die prematurely from preventable ailments. The healthcare system remains ill-equipped for aging populations.

Hospitals have no special wards for the aged, and home-based care is almost non-existent. The elderly are therefore caught in a vicious cycle of physical decline and social abandonment. We have become a nation that values youth over wisdom, wealth over worth, and profit over compassion.

Today, the story of many Nigerian seniors is one of quiet suffering. What we are witnessing is not just an economic problem; it is a moral decay. As I asserted in the last column, the value of Omoluabi, that noble character that binds respect, empathy, and gratitude, has been replaced by raw materialism. Many young people now see their aged parents as burdens rather than blessings. Modern life has ushered in an age where the old are seen as obsolete, and youth is glorified above wisdom. The moral compass has shifted. Where once it was a taboo to raise one’s voice at an elder, today it is almost fashionable to disregard them. The race for survival has drowned the echoes of conscience.

Our sense of collective responsibility has been eroded by the philosophy of “every man for himself.” The rise of materialism and the decline of empathy have diluted traditional norms of filial piety. What was once considered taboo, placing one’s aged parent in a home, ignoring their needs has now become commonplace. Migration has worsened the crisis. Many professionals, in search of greener pastures, live thousands of miles away from their aged parents.

They send remittances, yes, but money cannot replace presence. Love cannot be outsourced. Our old people are becoming, to borrow a phrase, orphans of modernity, left to navigate loneliness in the name of progress. The physical and emotional distance has weakened the culture of constant care. In this context, elderly people become “orphans of progress”, victims of development that excludes them.

At the policy level, the Nigerian state has not fared any better. There is little evidence of institutional compassion for the elderly. Although the National Senior Citizens Centre (NSCC) was established in 2021, it remains largely dormant and underfunded. Most of our social protection schemes, like conditional cash transfers or community-based health insurance, rarely reach the elderly in rural areas who need them most. There is no coherent national aging policy, no universal health insurance for seniors. There is also a lack of comprehensive data on Nigeria’s aging population, which impedes policy planning.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, persons aged 60 and above constitute about 5% of Nigeria’s population, a figure projected to rise significantly in the coming decades. Yet, the absence of an inclusive aging policy framework means that Nigeria is unprepared for the demographic shift.

Compare this to South Africa, where old-age grants provide lifelines to millions, or Ghana, where social pensions reduce elderly poverty. Kenya has implemented old-age grants and community-based elderly programs. In Nigeria, our senior citizens are invisible in national budgeting. Their suffering is treated as a private affair rather than a public concern. Nigeria, by contrast, still treats elderly welfare as a matter of charity rather than citizenship right.

To make matters worse, corruption and inefficiency often sabotage even the little that is designed for their welfare. We have turned a generation of givers into beggars. In this vacuum, faith-based and civil society organizations have become the thin line between survival and starvation for many seniors.

Churches, mosques, and NGOs organize occasional feeding programs, medical outreaches, charitable visits and support homes for abandoned elderly people. Yet, these efforts, though noble, are fragmented and unsustainable. A few NGOs, such as the Tony Obuh Foundation and the Geriatric Association of Nigeria and St Paul’s Senior Citizens Foundation., advocate for elderly rights and healthcare. True societal care cannot depend on seasonal philanthropy.

It must be institutionalized,anchored on state responsibility, community participation, and legal protection. Faith-basedinstitutions must move beyond charity to advocacy,pressuring governments to create enduring systems of elderly welfare. Investing in elderly welfare is not a wasteful expenditure, it is an investment in social stability and intergenerational continuity. Seniors play critical roles as caregivers to grandchildren, as moral mentors, and as repositories of cultural continuity. Some may argue that Nigeria has too many competing priorities, youth unemployment, insecurity, and poverty, than to invest in elderly care. But this is a false dichotomy. A nation that neglects its elders undermines its own moral and social stability. Furthermore, creating a structured care economy for the elderly, through geriatric centers, community nurses, home-based care services, and pension insurance, can generate employment, especially for women and young caregivers. Countries that have embraced “silver economy” models have found that elderly care can contribute meaningfully to GDP while enhancing social cohesion.

Caring for the aged istherefore not a drain; it is an investment in intergenerational balance. A society that neglects its elders erodes its moral foundation. If Nigeria must reclaim its humanity and restore dignity to its elderly, then the care of the aged must become a national priority. Towards this end, the National Assembly, and by extension, the State Assemblies must enact a comprehensive elderly care law that provides a legal framework mandating state responsibility for seniors’welfare, including access to healthcare, housing, and income support.

This should be the law that defines and protects the rights of senior citizens. The current National Senior Citizens Centre can devolve to all levels of government in Nigeria and be strengthened with proper data collection, or alternatively, funds be provided in the national budget for disbursement to States and Local Governments for the care of the seniors. In that regard, these levels of government will then establish senior recreation centres, andcommunity volunteers assisting the aged with food, healthcare, and companionship. I must not pretend that except properly monitored, it could be another cesspit of corruption. Universal Health Insurance for Seniors must be put in place.

No elder should die because they cannot afford drugs, diagnostics or hospital bills. Geriatric care should be free or heavily subsidized. The society must promote community-based living models which promotes community homes and neighborhood volunteers networks that ensures no elderly person is left unattended. Moreover, education and moral reorientation must be triggered by schools, religious homes and the media in order to regenerate our values of respect, gratitude, compassion and intergenerational solidarity. For those in the formal sector, pension arrears must be cleared promptly, and old-age grants extended to informal workers. These are not acts of charity but of justice. The elders of today were the workers, teachers, farmers, and parents of yesterday. They deserve not pity but dignity.When we abandon our elders, we dim the torch of wisdom that lights our collective path. The Yoruba say, Bi omode ba subu, a wo iwaju; bi agba ba subu, a wo eyin. When a child falls, he looks ahead; when an elder falls, he looks back. Our elders are the mirror of where we are coming from. To neglect them is to erase our past and compromise our future. Nigeria’s neglect of its senior citizens is not merely a social failure but a moral indictment.

To abandon those who once built our homes, taught our lessons, and laid our foundations is to sever our link with history. In a society where the young have no models, and the old have no comfort, what then becomes of posterity? Nigeria must rediscover that delicate balance between progress and compassion, modernity and morality. The future will judge us not by the highways we built or the skyscrapers we raised, but by how we treated those who once carried us on their shoulders. It is time we remembered that to honour the aged is to honour our roots. In the words of another Yoruba wisdom: A kii fi agba se’nu, a fi agba se’le. We do not disregard elders; we build our foundation upon them.

Besides, the actualization of this also has the multiplier effects of reducing corruption in public office as well as desperation for the same. The fundamental issue of insecurity at old age remains a propellant for avarice in public office. Let us rebuild Nigeria on that foundation of gratitude. Nigeria must therefore rise to restore honor to its seniors, not as an act of pity, but as an act of justice and gratitude. A society that honors its elders secures its own future. The torch of wisdom must not be allowed to fade.

I must register the fact that beyond my concern for the seniors overtime, due to the fact that my late mother enjoyed the best of such care as an American citizen while sojourning in America prior to her transition; this intervention was triggered by my former Biology teacher, Mrs Esther Aworinde, who alongside her late husband , Dr Iseoluwa Aworinde, had in the last almost threedecades established a seniors’ care centre in the country; and who two weeks ago engaged me on her thought to convert her late husbands’ magnificent hospital building into a geriatric hospital.

While not discouraging her per se, I had laid out the huge implications of the attempts, and the outcome of the conversation probably discomforted her. My analysis of the import would seem to me not to have fanned her optimism further. The only consolation I had for her, noticing her dull disposition afterwards, is the suggestion to partner with the State Government in actualizing the passionate dream. Hopefully, this will see the light of the day ultimately.