Lagos APC’s Crisis of Democracy: Internal Strife and the Risk to President Tinubu’s Stronghold

Nigeria’s ruling APC is teetering on the edge of self-inflicted damage in Lagos State. As the July 12, 2025 local government and LCDA elections approach, bitter infighting has replaced unity. Party stakeholders warn that internal divisions and the imposition of candidates by powerful insiders threaten both the party’s credibility and its electoral prospects. In community after community, aspirants and their supporters are openly rejecting top-down arrangements, insisting on genuine primaries. If Lagos APC leaders persist in sidelining grassroots voices—often invoking President Tinubu’s name to justify undemocratic candidate selections—they risk alienating voters and inviting legal disaster.

This crisis is more than procedural; it is a dire warning that “Lagos State APC is for sale” and that democratic norms must be defended, or the party’s dominance could crumble, even in its traditional stronghold.

Historical Apathy: Plummeting Turnout at Lagos LG Polls

Lagos has long suffered chronic voter indifference in local elections. Civil society observers describe turnout as “abysmally low.” For example, in the 2021 council polls, only an average of three parties appeared on ballots, and many polling units were nearly empty by late morning. This trend echoes a decades-long decline: while official records suggest a 41% turnout in the 1999 transition elections, more recent figures have often dipped into single digits.

Voter turnout in Lagos declined from an estimated 41% in 1999 to just 6% in the 2021 local-government elections. Even the much-anticipated “youth wave” of 2023—sparked by the EndSARS movement and amplified via social media—only pushed presidential-election turnout to 29%, still below the national average of 32%. Paradoxically, Nigeria’s most literate, urbanized, and economically vibrant state has become the capital of voter apathy.

Politically, Lagos has been dominated by the same ideological lineage since 1999: Alliance for Democracy (AD) → Action Congress (AC) → Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN) → All Progressives Congress (APC). The party currently holds the governorship, 38 out of 40 seats in the State Assembly, and every LGA/LCDA chairmanship. While opposition forces occasionally win federal constituencies—such as the PDP in 2015 and the Labour Party in 2023—they struggle to establish strong local structures. This “hegemonic but brittle” dominance shapes citizens’ perceptions: elections seem non-competitive at the local level but unpredictably fluid at higher tiers, fostering selective participation.

Drivers of Disengagement Are Multi-Layered

The causes of voter apathy in Lagos are complex. Structural issues like 42% youth unemployment, severe housing pressure, and average commuting times of 2.8 hours per day make voting a low priority. Institutional dysfunction also plays a role: LASIEC local polls are widely seen as pre-determined. The ruling party has captured 376 of 377 councilor seats over the last three election cycles.

Psychologically, the trust deficit is staggering: only 18% of Lagosians told Afrobarometer in 2022 that “elections enable voters to remove bad leaders,” a sharp drop from 44% in 2005.

Though electoral violence is sporadic, it looms large in public memory. CLEEN Foundation recorded 63 incidents across three LGAs in 2023, mainly in riverine areas where turnout crashed to below 10%.

In 2021, electoral observer Yiaga Africa noted that voters were “absent in some polling units as of 11am.” This sustained apathy has left Lagos councils with dangerously thin public mandates. Once a source of grassroots energy, the APC has slipped into quiet resignation. The only way to reverse this demoralization is to ensure party primaries and elections are truly inclusive. Yet, current signals suggest the opposite: rather than energizing members, APC leaders appear determined to repeat the very mistakes that have alienated voters.

The consequences are serious. Governments elected by dwindling minorities suffer legitimacy crises, weakening their ability to tax, reform, or rally citizens during crises. Local councils—constitutionally tasked with primary healthcare and basic education—drift into unaccountability. LASIEC reports show 27 councils failed to submit audited accounts between 2017 and 2021, with minimal public outcry due to voter disengagement.

“Baba Sope” Politics and Imposed Candidates

Reports from across Lagos point to a surge in what insiders call “baba sope” politics—candidate imposition by godfathers and emerging cabals, often operating from Abuja. In Ojokoro LCDA, a faction of APC chairmanship hopefuls publicly rejected a purported consensus candidate. In a defiant statement, they declared: “No individual or clique has the right to impose candidates against the will of the people. Ojokoro is not for sale. The people must decide.”

Other aspirants echoed this sentiment, dismissing media claims of a pre-arranged outcome as a “false, deceptive” ploy to subvert democracy. These grassroots leaders demand transparent balloting and insist every aspirant must test their popularity at the local level.

Similar dissent erupted in Agege LGA, where party leaders pushed for the son of the Lagos Assembly Speaker, Rt. Hon. Mudashiru Obasa, to clinch the chairmanship. At a stakeholders’ meeting, youths and elders held placards saying: “Obasa should not impose a chairman on us” and “You can’t bring a stranger to lead us.” One protest leader warned: “We reject any attempt to sideline loyal party members. Let everyone test their strength at the primaries.”

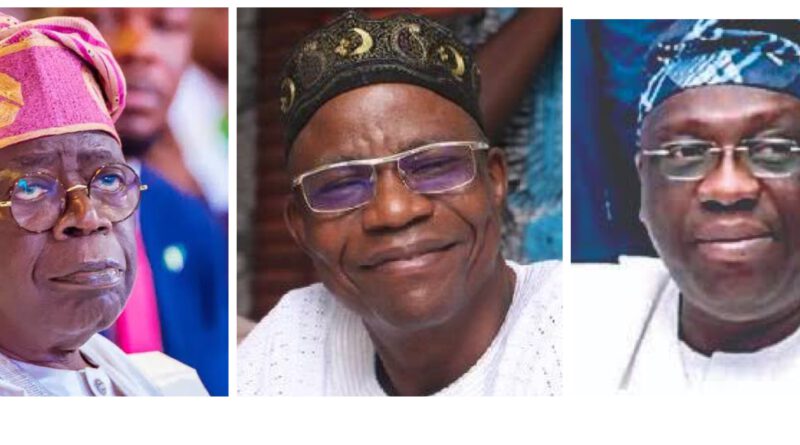

Even President Bola Ahmed Tinubu was drawn into the controversy. According to Vanguard, Tinubu reportedly nullified the endorsement of Obasa’s son and instructed that only “popular candidates” from “fair and open contests” be fielded. Yet, observers suspect another protégé may have been quietly anointed under Tinubu’s oversight.

This irony—invoking democracy while enforcing consensus—has deepened mistrust. It signals to voters that APC is more focused on imposition than representation, a mistake that has caused unrest in past primaries.

The Demographic Clock Is Ticking

Between 2023 and 2027, 1.7 million Lagosians will turn 18. If even a quarter of them vote, they could decide Senate and House races. Yet INEC’s bottlenecks persist. Its Continuous Voter Registration (CVR) portal closed nine months before the 2023 elections, disqualifying an estimated 317,000 Lagos youths. Unless CVR is reformed and expanded to tertiary institutions and malls, history could repeat itself.

Centralized Primaries and Screening Controversies

The Lagos APC’s approach to primaries is drawing further criticism. All screening and delegate selection activities were centralized at the party’s Acme Road secretariat in Ogba. Tribune reports that 470 aspirants were screened between April 29 and May 3, with 432 cleared for chairmanship primaries. The rest were disqualified for administrative reasons like invalid PVCs or fake certificates.

More controversially, the party has opted for indirect primaries, where only accredited party executives vote—not the general membership. This contradicts the party’s constitution, which grants local government executives authority to organize their own primaries.

Veteran APC legal adviser, Dr. Muiz Banire, warned in 2017 that centralized primaries violate party rules. He emphasized that the APC Constitution gives council-level executives the power to designate primary venues. Other APC chapters, like Benue, follow this decentralized approach. Lagos leaders ignored this and forged ahead.

This has sparked rumors of manipulation. Some aspirants say the screening resembled a “cash-and-carry” operation—particularly in areas like Coker-Aguda LCDA, where APC has historically struggled. Party insiders whisper of an “Aso Rock cabal” picking candidates behind closed doors.

Without transparency, invoking the President’s name to impose loyalty candidates breeds resentment and disengagement. When activists see leaders “planting” candidates, campaign enthusiasm dries up—and so does voter mobilization.

Undermining the Incumbency Privilege

Another flashpoint is the fate of sitting chairmen. Traditionally, incumbents enjoyed a “right of first refusal”—a gesture of loyalty and stability. In 2018, then-Governor Tinubu granted automatic tickets to 18 chairmen in exchange for their support.

But this tradition is crumbling. The current screening list shows only a few incumbents running unopposed—Surulere’s Sulaiman Yusuf, Iba’s Jibril Yisa, Ijede’s Motunrayo Alogba, and Lekki’s Kasali Bamidele. Most face multiple challengers.

Many returning chairmen feel betrayed. In ethnically diverse LCDAs like Coker-Aguda and Agboyi-Ketu, parachuting in unpopular outsiders risks alienating local blocs. One Abuja source warned that sidelining loyal incumbents could backfire and drive defections to opposition parties.

Ignoring party veterans is politically dangerous. These individuals know their wards. Sidelining them undermines not only structure but also local morale.

Legal Pitfalls: Section 84(8) and APC v. Marafa (2020)

Beyond politics, legal risks loom large. The 2022 Electoral Act introduced key reforms. Section 84(8) mandates that any indirect primary must involve democratically elected delegates. No handpicking. Any deviation violates the law.

Legal experts stress that appointing delegates—rather than electing them—flouts the Electoral Act. Section 84(13) is unambiguous: if a party fails to follow the rules, its candidate must be excluded from the election.

In APC v. Marafa (2020), the Supreme Court voided the APC’s entire list of candidates in Zamfara State for violating internal democracy. Lagos APC must heed this precedent or risk catastrophic losses—even before ballots are cast.