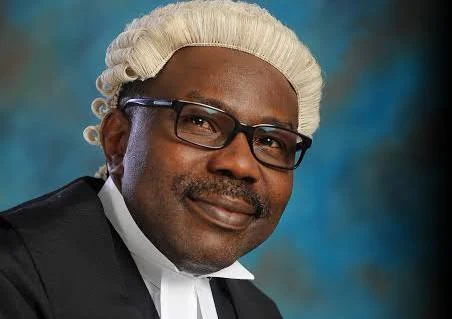

Waterless offices, worthless governance – Dr. Muiz Banire

Water is life. This timeless maxim captures the centrality of water to human existence, health, and dignity. Yet, across Nigeria, a disturbing paradox persists: government offices and public institutions that ought to symbolize order, hygiene, and civic responsibility often lack the most basic of amenities: clean, running water. Water, they say, is not just a need but a right of existence. Yet, across our land, particularly within the precincts of government offices as said above, one finds a growing irony, institutions built to serve the public are themselves dry and desolate, devoid of running water, devoid of dignity.

From federal secretariats in the capital to local government offices in remote towns, one encounters dry taps, broken boreholes, and water closets rendered unusable. This absence of water, though often dismissed as a mere infrastructural lapse, represents a deep-seated governance failure with far-reaching implications for public health, productivity, and national image. Walk into many local government secretariats today, and you are greeted not by hum of efficiency but by smell of neglect.

Toilets turned into waste chambers, taps that have long ceased to flow, and broken boreholes standing like tombstones of abandoned promises. In some government establishments, staff carry buckets from nearby vendors just to flush the restrooms. Others trek to neighbouring compounds with their bottles and basins, hoping for a drop to quench necessity. In the metropolitan government establishments, sachet water, popularly known as ‘pure water’, bridge the vacuum as government workers and visitors have to make do with them. This is not fiction; it is our sad reality.

It is a bitter irony that in many government offices, ministries, parastatals, and public schools, officials, charged with policymaking and service delivery, operate in environments where even handwashing after toilet use becomes a luxury. Visitors to government secretariats or other public institutions, particularly schools, are greeted by pungent odors from toilets that have long ceased to flush. In many cases, staff are compelled to fetch water from nearby wells, street vendors, or even pprivate water boreholes taps kilometers away.

The irony becomes sharper when one considers that some of these same offices host departments of water resources, health, or sanitation. The absence of water in public offices is not merely an infrastructural issue. It is symbolic, a reflection of a state that has lost touch with the essentials of governance. It is a reflection of systemic decay, misplaced priorities, and governance inertia. How can a Ministry of Health operate in a building where even handwashing after using the toilet is an ordeal? How can a local government environmental office preach sanitation when its staff cannot access water to clean their own facilities?

When a house begins to collapse, one must first look to the foundation. Our foundation of governance is weak, not because we lack grand policies or global visions, but because we ignore the small, vital things that make human life dignified. These waterless conditions send a hypocritical message that undermines public health campaigns. Citizens lose faith in government health advisories when the very custodians of such policies live contrary to them. The situation is akin to the rickety state of most of the enforcement vehicles used by government and security officials in the enforcement of roadworthiness of private vehicles. What an irony and contradiction always! Water, electricity, sanitation, these are the first indicators of a system that works. Their absence tells a louder story than any ministerial briefing can. These are not luxury as we seem to be painting.

The absence of them is a suggestion of a symbol of governance gone dry. This situation surpasses mere inconvenience; it reflects a broader neglect of maintenance culture and public accountability. It is emblematic of a state that builds structures without systems, inaugurates projects without sustainability, and values appearances over functionality. What many fail to realize is that water scarcity in public institutions is not a matter of comfort; it is a matter of public health.

The workplace becomes an incubator of diseases when water is absent. Toilets that cannot flush, hands that cannot be washed, and floors that cannot be cleaned turn offices into silent health hazards. The health consequences of water deprivation in public institutions are profound and multifaceted.

A lack of clean water transforms offices into breeding grounds for diseases, undermining the very notion of a safe workplace. Without water, basic hygiene collapses. Unflushed toilets and unwashed hands lead to outbreaks of diarrheal diseases, typhoid fever, skin infections, and cholera. Offices without running water become silent incubators of pathogens that staff unwittingly carry home, spreading illness to families and communities. These are some of the hidden health crises. Yet we often treat them as invisible. The spread of disease does not respect officialdom; the bacteria on an unwashed hand can travel from the office desk to the dining table, from the government building to the home. Àìsàn kò mọolóyè, illness knows no rank. For female workers, the situation is even more distressing. Without water and sanitation facilities, women, who constitute a large proportion of the public service, suffer disproportionately. The absence of water and sanitary facilities in offices exposes them to discomfort, infections, and absenteeism. It is a violation of gender dignity and occupational health standards. Their menstrual hygiene becomes a daily challenge, a source of shame. What dignity is there in labour when a worker cannot access clean water in her own office and cannot access clean toilets? In desperation, some offices resort to open defecation or use of disposable containers and plastics for waste disposal, compounding urban sanitation challenges.

All these come with costs to dignity and productivity. There is a silent erosion of dignity that comes with working in such conditions. When civil servants spend hours fetching water before they can use a restroom, productivity plummets. Morale wanes. The workplace becomes a place to endure, not to excel. This aberration equally has dehumanizing and psychological effects on the employees. Working in a filthy environment erodes morale and self-worth. Public servants forced to endure unclean toilets, fetid smells, and unhygienic conditions experience diminished motivation, absenteeism, and stress-related ailments. Foreign visitors, development partners, and investors who encounter these realities often leave with a lasting impression of dysfunction.

They see not a country of great potential but one that cannot maintain the basics of decency. We may organize summits on public sector reform, but as long as the taps in our offices remain dry, our credibility leaks like a broken pipe. The reverse is also true , when the source dries, the riverbed follows. When public offices cannot maintain water supply, what moral ground do we have to demand sanitation compliance from markets, schools, or hospitals? The question then is what is responsible for this? Several interrelated factors explain this persistent scourge.

Although most public buildings are constructed with water supply systems, tanks, boreholes, or municipal connections, but are left to deteriorate soon after commissioning. Pumps break down, pipes corrode, and storage tanks collapse without repair budgets, a simple case of neglect of infrastructure maintenance. There is also the challenge of poor budgeting and mismanagement.

Often times, recurrent budget rarely prioritize facility maintenance. Where allocations are made, they are often misapplied or diverted. Budgets for maintenance are often swallowed by bureaucracy, and even where funds are approved, mismanagement dries them up before they reach the taps. The absence of transparent facility management frameworks worsens the day. Lastly on this, facility management is hardly contemplated alongside projects design and execution, leading to neglect and eventual collapse.

Where there is even provision made, the over-centralization of control command and bureaucracy hampers implementation. The centralization of simple repairs requiring Abuja approval before fixing a pump in Akure ensures that decay becomes permanent. Simple repairs that could be handled locally often require approvals from distant headquarters, creating bottlenecks and prolonged neglect. Fundamentally, there is also the challenge of urban water supply. The inadequacy of public water utilities compounds the problem. In most Nigerian cities, State water corporations provide erratic service, forcing even ministries and agencies to rely on private boreholes which themselves require regular maintenance and power, and constitutes threat to the aquiver. The larger dimension of the ugly picture above is that water scarcity in public offices transcends health, they ripple across the economy and social psyche. As opined above, for visitors, investors, or international partners, such neglect reinforces stereotypes of Nigerian bureaucracy as inefficient and unserious.

A first-time visitor to most government buildings with dry taps and filthy restrooms cannot be expected to take government policies on sanitation seriously. The net implication of this is that citizens perceive the absence of water in public offices as a metaphor for governmental failure to provide essential services. It deepens cynicism toward public institutions. Although, legally, Nigeria’s Constitution may not explicitly guarantee access to water, but the right to a healthy environment is enshrined in Section 20 of the 1999 Constitution. In international instruments also, the right to life is now intrinsically now tied to the right to water.

The National Water Resources Policy and National Environmental (Sanitation and Waste Control) Regulations, 2009 further mandate public institutions to maintain sanitary facilities. Therefore, the absence of water in public offices constitutes not only an administrative lapse but also a violation of public health regulations and citizens’ rights to dignity. Moreover, Nigeria is a signatory to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6, which commits nations to ensure “availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.” Yet, as with many good policies, implementation remains the Achilles’ heel. When public institutions fail to meet this minimum standard, they betray both domestic and international obligations. The further import of the above is that the public office itself becomes a public offense. The true tragedy therefore lies in what this decay symbolizes.

A public office should be the model of order, hygiene, and civic discipline. But when citizens visit ministries or agencies and find filthy restrooms, foul odours, and dry taps, it reinforces the popular cynicism that government cannot manage even itself. It becomes, quite literally, a public offense. A nation that cannot provide water in its public offices has no moral right to lecture its citizens on cleanliness. “Ile la ti n ko eso rode.” Charity, they say, begins at home. Good governance begins in the workplace, in the running tap, the clean restroom, the maintained facility. As expected, surrendering to fate is not an option, but addressing this scourge demands a multipronged strategy rooted in accountability, planning, and civic responsibility. The solutions are neither new nor complicated. What is lacking is the will. Every public institution must adopt a routine maintenance framework with clear accountability. Every public building must have a dedicated facility management plan with budgeted maintenance schedules.

Water supply systems should be treated as critical infrastructure, not optional amenities. Sanitation audits should be as regular as financial audits, and must form part of institutional assessments. Ministries of Environment and Public Service should collaborate to create annual “Sanitation Compliance Ratings” for public offices. Maintenance must be decentralized. Local heads of departments and agencies should be empowered and held accountable for the functionality of their office utilities. Routine inspections and sanctions must accompany this delegation. Facility management should no longer be treated as a luxury, but as the foundation of public health.

There is also the need to embrace modern innovations, solar-powered boreholes, rainwater harvesting, and smart water systems can reduce dependency on erratic public water supply. Partnerships with NGOs and private sector actors in the WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) sector can bring sustainability. But beyond technology lies the human factor, discipline, responsibility, and pride in the workplace. The public servant must rediscover a sense of ownership over public assets. We must heed the Yoruba proverb that warns that public property always suffers neglect:“Eshin ajobo, ebi lo n paa ku. If the earth itself is 78.4% water, it means water is life and yet, we do not have enough to live a clean life as a result of neglect and remissness. What we do with water endures; cleanliness and maintenance breed respect and productivity. Water, as a symbol of purity and renewal, must return to the heart of public service. Truth be told, the absence of water in our public offices is a metaphor for the state of governance in Nigeria, dry, neglected, and in need of renewal. Restoring water to our offices is not just about hygiene; it is just about restoring dignity, order, and humanity to the public service. If the government cannot make water flow in its own offices, how can the people trust it to make prosperity flow in their lives? The solution begins with a simple act, turning the taps back on, literally and metaphorically.

The restoration of water to every public office in Nigeria therefore would not only safeguard health but also restore the dignity of work, reaffirm citizens’ faith in government, and signal that the state takes its own policies seriously. After all, true governance begins not in the grandeur of policies, but in the everyday details of human welfare, the clean toilet, the flowing tap, and the dignified workplace. Let the flowing tap become the symbol of a new kind of governance, one that values life, dignity, and the small details that make civilization humane. We must note that when the tap dries, it is a metaphor for poor governance.