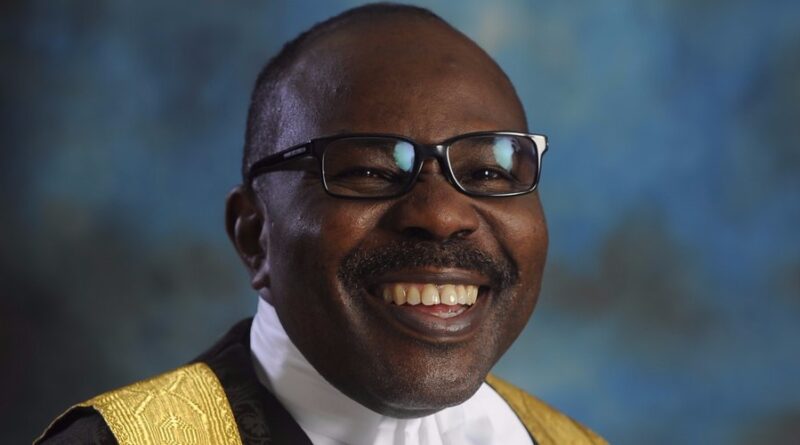

When doctors die in silence: A national indictment – Dr. Muiz Banire

In several of my past interventions ( In my column in The Sun published 17th December 2020, titled “Health care delivery: The capital market option”

https://www.sunnewsonline.com/health-care-delivery-the-capital-market-option/ , In my piece titled “Our Fate After COVID-19” published 6th April 2020

https://theinterview.ng/2020/04/06/our-fate-after-covid-19/ , In my column in The Daily Sun Newspaper published 22nd April 2021, titled “COVID-19 donations: Call for probity, accountability” https://www.sunnewsonline.com/covid-19-donations-call-for-probity-accountability/ , In my column in The Daily Sun Newspaper published 6th October 2022, titled “Mental health crisis in Nigeria” https://www.sunnewsonline.com/mental-health-crisis-in-nigeria , In my column in The Sun published Thursday, November 23, 2023, titled “Cost of Democracy vs Dividends of Democracy”

https://sunnewsonline.com/cost-of-democracy-vs-dividends-of-democracy/ , In my column in The Sun published 24th July 2025, titled “When a president dies”https://thesun.ng/when-a-president-dies/, see my column in The Sun, published on 5th January 2026 titled “When sickness meets poverty https://thesun.ng/when-sickness-meets-poverty/”), I have interrogated the disturbing deficits in Nigeria’s healthcare delivery system, deficits that were brutally exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the height of that global crisis, lamentations filled the air. Our leaders openly acknowledged the deplorable state of our health facilities across the country and solemnly promised immediate rejuvenation. Billions of naira were reportedly mobilised in the name of rescuing the sector.

I vividly recall the emotional admission and appeals of the then Secretary to the Government of the Federation, Boss Mustapha, as well as the huge donations announced by government and private actors, which were expected to be administered under the stewardship of the then Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, Godwin Emefiele. As is often the case with us, the noise made the headlines; the promised action quietly evaporated. Today, years later, we are confronted with the same grim reality. Only recently, the coordinating Minister for Health publicly lamented the abysmally poor release of capital expenditure to the health sector, another gloomy reminder that our past, present, and perhaps even our future remain trapped in a vicious cycle of neglect. However, this intervention is not directed primarily at the visible infrastructural gaps in our healthcare system. Rather, it seeks to advance the case of the human beings who sacrificed everything so that the rest of us might live and live healhy.

It is aimed at re-echoing and amplifying the message contained in a recent and deeply unsettling discourse authored by M. A. Suwaidin. Professor Suwaidin’s piece paints a disturbing picture of how quickly society vilifies and condemns medical doctors whenever deaths occur, particularly when such deaths involve celebrities or their relatives, without patience, investigation, or appreciation of context. We rush to judgment, fuelled by emotion and social media outrage, rarely pausing to interrogate the circumstances under which such tragedies occur. Even where negligence is evident and deserving of sanction, fairness demands due inquiry. Yet, what of the many instances where doctors are not at fault, or worse still, where they lose their own lives in the course of saving others? Such cases abound. As the Professor poignantly observed: “Yet, almost unnoticed, a doctor dies after contracting Lassa fever in the line of duty—infected while treating a patient.

No hashtags. No outrage. No national mourning. Just a quiet burial and a grieving family left to cope alone.” If we choose to forget the numerous casualties under such circumstances, we surely cannot forget the late Ameyo Adadevoh, who paid the ultimate price while treating an Ebola patient, thereby saving millions of Nigerians from a national catastrophe. Beyond the commendable recognition accorded her by the then Governor of Lagos State, Babatunde Fashola, how else have we truly celebrated her sacrifice? How many of such doctors have trended, been memorialised, or honoured proportionately for paying the supreme price in the line of duty? More importantly, have we ever paused to interrogate the absence of adequate safety valves for medical personnel, particularly in our public health facilities? Have we sufficiently acknowledged the daily dangers to which they are exposed?

These questions validate Professor Suwaidin’s assertion that: “The death of a doctor from an occupational infection is not just a personal tragedy; it is a systemic failure. It raises uncomfortable questions about workplace safety, institutional support, insurance, compensation, and preparedness. But these questions are rarely asked because the victim is not famous, not wealthy, not trending.” Have we, as a society, ever truly interrogated the safety of doctors, much less their general welfare? Have we reflected on the negligence that arises from chronic overwork, understaffing, lack of essential equipment, and emotional exhaustion? Doctors are not magicians, nor are they spirits.

They operate within the limits of human knowledge and available facilities. This truth is humbly captured in the motto of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi-Araba: “We care, God heals.” There is something profoundly unsettling, indeed tragic, about a society in which those trained to preserve life are themselves left to perish quietly, unattended, and uncelebrated. When Doctors Die in Silence, as articulated by Professor Suwaidin, is not merely an essay; it is a mirror held up to our collective conscience. It exposes, with painful clarity, a moral contradiction at the heart of our healthcare system: the healers are often forgotten, and those who spend their lives fighting death are ultimately abandoned to it. A doctor’s life is anything but ordinary. It is forged through years of sacrifice, long nights of study, exhausting residency programmes, relentless call duties, emotional immersion in suffering, and a professional oath that subordinates personal comfort to the survival of others.

Yet, paradoxically, when illness, exhaustion, or old age finally takes its toll, the very system that consumed their strength frequently withdraws its care. The silence surrounding the death of doctors is therefore not accidental; it is systemic, institutional, and deeply revealing of our national priorities. Doctors die not only from natural causes but from preventable exhaustion, untreated stress, occupational hazards, and inadequate access to quality healthcare, ironically within the institutions they once served. Many die without robust health insurance to cover terminal illnesses. Some die after years of unpaid pensions, delayed entitlements, and humiliating bureaucratic struggles. Others pass away quietly in rented apartments, far removed from the hospital wards where they once stood between life and death for countless strangers. Their deaths rarely provoke national mourning, policy review, or structural reform.

At best, they attract fleeting condolences; at worst, complete indifference. This silence is not benign. It is cruel. It tells the living doctor that loyalty to the system is a one-way obligation. It tells young medical students that devotion is rewarded with neglect. It tells the public that a doctor’s worth expires once utility diminishes. Most dangerously, it tells government that the erosion of morale in the health sector is an acceptable collateral damage. The silent deaths of doctors also expose a deeper societal failure to value service over spectacle. In a country where entertainers, politicians, and socialites are lavishly celebrated in death, the quiet burial of a doctor who saved thousands of lives represents a tragic misalignment of values. We applaud noise and ignore substance; we glorify wealth and trivialise sacrifice. Yet no nation survives for long when its saviours are treated as expendable. From a governance perspective, this silence is a damning indictment.

A state that cannot protect those who protect its citizens has failed in its most basic duty. Healthcare policy must go beyond infrastructure and equipment to include welfare, dignity, and post-service security of healthcare professionals. Functional health insurance, mental health support, enforceable work-hour regulations, prompt payment of salaries and pensions, and institutionalised recognition of service are not privileges; they are necessities. Anything short of this is exploitation disguised as patriotism. The public, too, must accept responsibility. We are quick to blame doctors during strikes, impatient during delays, and hostile when systems fail, yet painfully slow to empathise with the conditions under which they operate.

We forget that the exhausted doctor is still human, that the grieving doctor has emotions, and that the ageing doctor deserves care. We also forget that a deceased doctor left behind a bereaved and equally grieving family who ought to be taken care of and expected that care and nurturing would be provided by their deceased asset just buried under the ground as a result of untimely death. If society continues to consume doctors without compassion, the inevitable outcome will be burnout, brain drain that the country is currently experiencing, and death in silence, until there are none left to save us.

Professor Suwaidin’s intervention should therefore be read not merely as a lamentation but as a call to conscience. It compels us to ask uncomfortable but necessary questions: What becomes of those who gave their lives to our survival? Why must doctors die unheard? What does it say about us when we normalise such endings? In many cultures, a society is judged by how it treats its elders and its servants (see my column in The Sun published on 23rd October 2025: The Vanishing Culture of Caring for Elders https://thesun.ng/the-vanishing-culture-of-caring-for-elders/ ). By that standard, the silent deaths of doctors represent a collective moral failure. We must deliberately reverse this narrative, through policy, culture, and conscious public action.

Doctors should not die in silence; they should live with dignity and be remembered with honour. As Professor Suwaidin rightly concluded: “Healthcare workers are not expendable. They are not martyrs by default. Their sacrifice should not be normalised or ignored. Every doctor who dies in the line of duty deserves recognition, protection, and accountability from the systems that sent them to the frontlines.” Until we learn to care for the caretakers, our healthcare system will remain fundamentally broken, no matter how many hospitals we build or slogans we invent. A nation that allows its doctors to die in silence is, in truth, preparing its own slow and unceremonious decline.