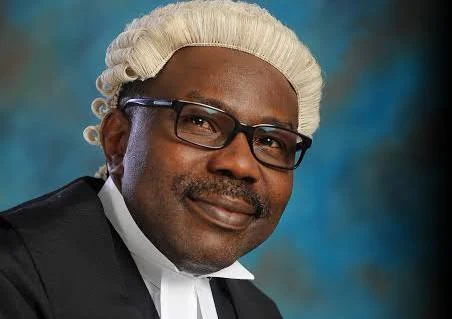

Plight of retired military officers in Nigeria – Dr. Muiz Banire

This conversation is borne out of my recent experience on the plight of my friend’s father who is a retired military officer and who rose to the rank of a General in the Nigerian Army before retirement. In the last few years, he has been unwell, thereby demanding what I consider to be serious medical attention. In the military men’s usual patriotic nature, he, just like other military personnel, insisted on being treated at the military hospital rather than any other hospital, private or public.

However, the best the military administration has done upon his retirement was to simply hand him theNational Health Insurance Scheme card which only covers basic ailments. As can easily be forecasted, most ailments suffered by these ex-service men are usually chronic due to the stress and trauma they have subjected their bodies to. The implication of handing them those basic cards is that such serious ailments are not covered by the insurance, thus abandoning them to their fate and that of their families. Those of them who are not lucky to have such support care from relatives or men of goodwill, end up withering away like leaves. When probed further, the Military hospital virtually confessed that they were not better than consulting clinics for minor ailments. Once the ailment requires specialist or consultants, such specialists and consultants are imported from outside and the fees must be commercially paid. Who then bears the brunt? The retired military men under treatment? This is the predicament of these ex-service men. Let us now take an excursion into the lives of these men, so as to know if they deserve the treatment we are meting out to them. Nigeria’s retired military officers are men and women who stood in the breach through civil war, peacekeeping missions, insurgencies, and innumerable internal security operations, carrying scars that uniforms once concealed and national memory too often forgets.

The parade ground fades; the medals gather dust; the bugle falls silent. Yet bills arrive monthly, illnesses do not salute rank, and obligations to family and society remain. Their plight is not a sentimental theme; it is a test of our national conscience and a barometer of how a republic values service. As the Yoruba say, ti a bá gbàgbé eni tí ó jáfún wa, ta ni yóò já fún wa lola? If we forget those who fought for us, who will fight for us tomorrow? These are officers who, from the aftermath of the Civil War (1967–1970), through the tumultuous decades of coups and counter-coups, to the more recent era of constitutional democracy, have absorbed shocks that would buckle most institutions. They served abroad under the ECOWAS Monitoring Group, wore the blue helmets of the United Nations, and, at home, responded to upheavals ranging from militancy in the Niger Delta to Boko Haram’s insurgency and banditry. Many retired with little fanfare, some with disabling injuries, and others into a society whose systems were not designed to make their transition dignified or even predictable. The old regime of defined benefits and gratuities was erratic; periodic reforms tried to impose order, but implementation often faltered. Verification exercises became a grim ritual wherein elderly veterans queue in the sun and rain to “prove” they were alive.

A veteran’s greatest enemy, it sometimes seemed, was not the adversary on the battlefield but a file lost in a ministry or an algorithm that failed to reconcile digitized records with analogue service books. In this gap between policy and practice, poverty found many who once commanded battalions. Even where he survived this ordeal, the economics of a typical retired officer’s life is a relentless arithmetic. Pensions rarely keep pace with inflation; arrears, when they occur, cascade into rent defaults, school fees crises, and medical postponements. Even when reforms promise harmonization and upward reviews, delays blunt the impact. Those who retired decades earlier often receive substantially less than peers who left later, despite comparable years of service, thus creating a hierarchy of hardship. Compounding this is the nature of military careers: constant transfers, operational deployments, and a work culture that discourages side hustles which leaves many officers with limited personal enterprises at retirement. By contrast, civilian professionals often moonlight or invest steadily over long horizons. The officer’s comparative disadvantage shows up starkly at 55 or 60, when the pay stops but the responsibility to the family, immediate and extended,remains, particularly in a society where public esteem does not necessarily translate into economic support.

As I indicated above, the attraction or inducement to engage in this conversation arose from the medical challenges they confront after retirement. For many veterans, healthcare is the most urgent and unforgiving front. Military service exacts a cumulative toll: musculoskeletal injuries, hearing loss, post-traumatic stress, hypertension, and metabolic disorders shaped by decades of stress commands and operational diets. Accessing quality care, however, is a labyrinth. When coverage exists, it may be geographically distant, poorly funded, or narrowly scoped as remarked above. Where service hospitals provide for retirees, capacity is strained and medications inconsistent. Private clinics, even within the military hospitals, demand out-of-pocket payments that pensions cannot sustain. The mental health dimension is often the quietest tragedy.

Traumatic exposures from clearing IEDs to witnessing the aftermath of massacres, leave invisible wounds. Yet culturally, stoicism is prized; officers are trained to “soldier on.” Without structured screening, peer support systems, and confidential counseling pathways, untreated trauma metastasizes into depression, substance misuse, or family breakdown. A country that deployed these men and women ought to be prepared to debrief them humanely. This is where duty meets the waiting room. Regrettably, the society is unavailable for them at this point. As if this is not traumatic enough, most times they are not only with fragile roof but are homeless. Stable housing is the anchor of retirement. But the military life’s mobility, barracks postings, mission tours, temporary accommodation, often mean officers reach retirement without a home fully paid.

Cooperative schemes and mortgage products exist in theory; in practice, affordability, bureaucratic delay, and title insecurityderail the plans. The result is a paradox: an officer may have commanded a cantonment but lacks a settled address in civilian life. This housing insecurity has social consequences. When retirees scatter to far-flung towns without supportive networks, loneliness and marginalization increase. Conversely, barracks’ adjacent communities sometimes stigmatize ex-soldiers as “spent forces,” even as they casually call them in moments of local panic. A humane policy must therefore see housing not just as shelter but as a platform for community re-entry. The journey out of uniform is also a journey out of a powerful identity. In the military, an officer’s world is structured; routines, ranks, clear chains of command. Civilian life is ambiguous. Those skills that sustained operational excellence, that is, discipline, planning, team leadership, do not automatically translate into job offers.

Age discrimination narrows options; the private security industry absorbs some, but many roles are precarious, underpaid, and devoid of benefits. Dignity is a currency in short supply. Public ceremonies laud service on Independence Day as we shall observe in the next few days, but a veteran who must chase a file in a provincial office or beg a pharmacist for credit receives a different message. A society that signals “you are on your own” to those who once lived on call for the republic unwittingly erodes its moral contract with current service members.

Iku t’o n pa ojugba eni, owe lo n pa fun ‘ni. Yes, the Yoruba have captured it most profoundly. For those who are currently in service, the deaths of your peers, is a proverbial confirmation of your own mortality. Whatever happens to ex-servicemen is likely to be your fate upon your retirement. The question is why must the society be bothered? There are at least three pragmatic reasons for thisbeyond moral sentiment: The first bothers on national security. How a country treats its veterans signals to serving personnel, and to potential recruits, what awaits them. Poor treatment depresses morale, corrodes trust, and can push skilled operators toward private militias or foreign security markets. Evidence of this is already staring us in the face in cases of banditry, kidnapping and terrorism, amongst others. Retirees, with intelligence, community respect, and tactical experience, are critical assets for early warning systems and civic education, if we engage them. Secondly, social cohesion. Veterans are bridges between the state and the citizens in volatile communities.

They can mentor at-risk youths, organize neighborhood vigilance ethically, and model non-violent conflict resolution, roles that wither if poverty and bitterness prevail. Thirdly, historical continuity. Nations are stories we agree to tell together. Veterans carry living archives, lessons from campaigns, doctrines refined through hardship, and cautionary tales about political adventurism. If we let those stories die in penury, we amputate our institutional memory. The current operational regime for their care suffers many afflictions, amongst which are fragmented governance, data poverty and weak enforcement. Veteran affairs are spread across ministries, boards, and military formations with overlapping mandates and blurred accountability. In such fragmentation, no single entity is fully answerable for outcomes, and problems fall through institutional cracks. Accurate, up-to-date rosters of retirees, their health needs, dependents, and locations are often incomplete.

Without reliable data, budgeting is guesswork and targeting is crude. Even when entitlements are clear on paper, enforcing timelines, penalizing bottlenecks, and auditing leakages remain inadequate. The principle of “pay the soldier first” is not yet embedded. This is in spite of the fact that the country has made fitful strides in terms of digitization of records, periodic pension reviews, attempts at veteran databases, sporadic health coverage improvements. Yet these structural gaps persist. What then is the way forward? A credible response to the plight of retired officers must be comprehensive, measurable, and insulated from political mood swings. The following pillars offer a practical roadmap: The country needs to create or empower a single statutory body with end-to-end responsibility for veterans’ welfare: pensions, healthcare, housing, employment, and memorialization. It should integrate databases with the services, revenue authorities, and national ID systems; publish service standards; and be subject to independent audits. Its leadership must include veterans and health finance experts, not merely career bureaucrats. The country must enshrine in law a 30-day pension payment rule with automatic interest penalties for delays that are borne by defaulting agencies’ officials, not by the treasury. Mandate quarterly public dashboards showing on-time payment rates, arrears stock, and resolution times.

What gets measured gets done. Beyond the perfunctory provision that covers virtually nothing in point of the heath needs of the retired military personnel, there is urgent need to enroll all retired officers and their eligible dependents in a veteran-tier health plan that covers primary care, chronic disease management, essential surgeries, prosthetics, and mental health. This obtains in other large public corporations and private establishments. Link service hospitals to a referral network of accredited civilian facilities nationwide. Fund this through a dedicated line item, complemented by a modest defense surcharge on select luxury goods and ring-fenced sin taxes. Telemedicine can extend reach to rural veterans; mobile clinics can conduct quarterly outreaches for screenings. In addition, we need to institutionalize pre-retirement psychological debriefs and post-retirement check-ins at 6, 12, and 24 months. Train peer counselors among retirees; set up 24/7 confidential helplines staffed by clinicians conversant with military culture. Normalize care by integrating mental-health services into routine checkups with no separate queue that stigmatizes. To cater for their housing needs, we must scale up veteran-specific mortgage products with longer tenors, lower rates, and credit guarantees.

Prioritize retirees for serviced plots in new federal and state layouts; provide legal aid to resolve title disputes. Partnerships with credible private developers can deliver affordable, standardized designs, while cooperatives manage maintenance to preserve value. I often wonder what the various military propertycompanies are doing with their assets.

This is another pandora box that I do not intend to deal with herein but in the nearest future. It is suggested that the country launches a Veterans Skills Translation Programme that maps military competencies to civilian certifications: logistics to supply-chain credentials, signals to ICT and cybersecurity, engineering to facilities management, medical corps to community health. On the strength of this, we then offer short, intensive bridge courses with recognized certificates; incentivize private employers via tax credits for veteran hires and apprenticeships. Then encourage veteran-owned SMEs with preferential access to public procurement quotas and prompt payments. All these can be coordinated by the Armed Forces Resettlement Centre in Oshodi and other parts of the country towards enhancing its capability. Towards memorialization and civic integration, the country can build local memorial spaces in form of small, living museums and libraries in divisional headquarters where veterans can tell their stories to students, conduct leadership clinics, and curate oral histories. This symbolic respect reinforces material reform and is essentially necessary. Finally, the country must commission longitudinal studies on veteran outcomes in terms of health, income, family stability to guide policy iteration. We then publish anonymized datasets for researchers which validates the fact that evidencebeats guesswork. To actualize the foregoing, although defense is a federal preserve, these retired personnel served all Nigerians that constitute the polity. Hence, the question of bifurcation is immaterial in this regard. This implies that states can lead in practical ways: co-funding health schemes, allocating land, waiving local fees, and integrating veterans into community policing advisory councils. The private sector’s role on the other hand is twofold: employment and philanthropy. Corporations benefit from veterans’ discipline and leadership; formal veteran recruitment pipelines should be part of corporate governance scorecards. Meanwhile, foundations can fund mental health innovation, scholarships for veterans’ children, and entrepreneurship accelerators. Civil society and faith-based organizations, long present in the welfare space, should add a veteran lens to their programs, financial literacy workshops near cantonments, caregiving support groups for spouses, and legal aid clinics for pension disputes. Media houses can equally commit to an annual “Veterans Accountability Index,” ranking agencies by service delivery.

At this juncture, the question is not whether we can afford to care for veterans but whether we can afford not to. Consider the hidden costs of neglect: emergency hospitalizations from unmanaged chronic diseases, social disorder when trained but disaffected men become instruments in local conflicts, the recruitment crisis when service members see that loyalty is a one-way street. Smart investment reduces downstream costs. Moreover, ring-fencing funds, cutting duplication, and auditing leakages will often save money. In a country like United States of America, benefits of veterans range from general pensions for the veterans or their survivors.

The special pension is accruable to surviving spouses who has not remarried or unmarried dependent of a deceased veteran. There is also provision for disability payments for veterans who suffer, or sustain aggravated injury or disease while on active service. Where the injury is severe, extra money is made available. There is equally financial aid for education where such veterans are interested in further studies, or towards acquisition of new skills where desirous. The country also provided Aid and Attendance, as well as housebound benefitsthat cater financially for veterans and surviving spouses who require regular attendance of another person to assist in eating, bathing, dressing and toileting. Community care facilities are established in the immediate communities to serve as an option to bypass waiting for appointments ortravelling a long distance to a facility. With regard to the blind people, or those with impaired vision or even low vision, the blind rehabilitation services exist to cater for them. Also, in existence is what is called State veterans’ homes that provide services such as rehabilitation and skilled nursing, long-term care, residential care and dementia care for those in need. Telehealth helps the immobile veterans or those in remote areas in accessing routine health care services such as physical therapy and mental health appointments via technology that connects them to specialist in any part of the country.

For the invalid, home hospice care is available to provide comfort and support, particularly where they are at an advanced stage of terminal disease. This brings succour to them at this latter day. To address the challenge of housing, various home loans such as veterans’ home loans which assist members of the military secure mortgage loans to purchase a home is established and funded. The uniqueness of this is that the facilities grantable are guaranteed as the mortgage is administered through an approved lender. There is no need for extra collateral. Of further interest to me is the special adapted housing grants which offer cash benefits to veterans with certain service-connected disabilities which assist them in buying or remodeling a home to accommodate their mobility needs. As most of them are still agile and productive, there is the Employment Assistance Programs as well as resources to help them find job. This is usually provided by the States. Even on a less serious note, veterans desirous of adorning special plate numbers to recognize their ties in serviceare also privileged. All these are just a tip of the iceberg as there exist several countless opportunities to the veterans to the extent of making them never regretting their service to the nation.

At this stage, the point is that we need to keep faith with those who kept faith. Remember when the state deployed them as service men, retired officers did not negotiate conditions on a battlefield. They executed orders under flags they did not choose and in terrain they did not design. Now, outside the wire, they deserve predictability instead of pleading, systems instead of sympathy, and justice instead of charity. Nations are ultimately judged by how they treat their weakest and their worthiest. Our veterans are not supplicants; they are creditors to whom the republic owes a debt, both moral and material. The bugle, at last, is quiet. But the duty to keep faith with those who kept faith with us still calls. Let us answer it with policy that works, budgets that pay, clinics that heal, homes that shelter, and rituals of remembrance that teach our children that service was neither wasted nor forgotten, for if we safeguard the dignity of yesterday’s guardians, we fortify the resolve of today’s and earn the loyalty of those who will stand the watch tomorrow.This is the least action that we can take and state of emergency must be declared in this regard.