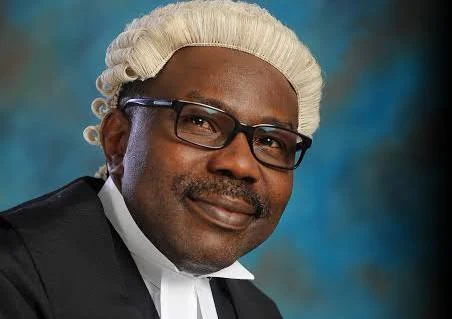

I am not a fool, I have integrity – Dr. Muiz Banire

I’m sure that Nigerians will be wondering why I am extending the congratulatory message to the Minister in the light of what transpired between him and the naval officer on Tuesday. I am doing so because on a typical day where such incident occurs, it is a panel of enquiry that will be ongoing after the demise of the subject. It is this survival luck of the Minister that warrants the congratulatory message otherwise a repeat of the “mad dogs” assault involving Chief M. K. O. Abiola and some military officers in the 1980s would have been a disaster. I salute the calmness and composure of the naval officer to whom I shall return later in the discourse.

In last week’s column, I examined the now-viral confrontation between the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory, Nyesom Wike, and Naval Lieutenant Commander Emmanuel Yerima over a disputed parcel of land in Abuja. I had hoped that the intervention would close the chapter. But every so often, an issue refuses to die because it speaks to deeper institutional malfunctions and national contradictions.

This is one of such. The comments, debates and sometimes misplaced indignation that have followed, compel a further inquiry, not because of any fascination with the political theatre, but because clarity is a public duty when confusion clouds civic understanding. A few readers, thankfully, an extreme minority, have expressed puzzlement over my earlier defence of the naval officer’s conduct. Their confusion appears to arise from a misunderstanding of Yerima’s status and obligations in the chain of command. The persistent question seems to be: why didn’t the officer simply step aside, negotiate, or allow the Minister of the FCT into the premises? Why didn’t he argue or debate the “title documents” with the Minister? Why didn’t he demand from his instructor the title documents? Why didn’t he interrogate the propriety of his deployment? These questions, on their face, seem innocuous.

But they reveal a fundamental misapprehension of how military structures function. Anyone who watched the video would have heard Yerima repeatedly saying that he was acting on “orders from above.” He did not claim personal ownership. He did not hint at personal interest. He did not invoke personal discretion. He invoked the military command structure, an indication that a superior officer had deployed him with a clear mandate: hold this location and prevent unauthorized access until otherwise directed. To ask whether Yerima could have refused that order is to ignore the foundational principle of military organization.

Under the military system, obedience is not advisory; it is compulsory. The doctrine is simple: obey the last order. It is obedience that keeps units coherent, missions effective, and discipline intact. A field officer has no authority to question the motive, legality, or documentation behind an order. His duty is to carry it out. Failure attracts consequences ranging from reprimand to court-martial, and in extreme cases, career termination or imprisonment. In the military, there is no room for individual improvisation when orders are clear. Yerima therefore had two lawful choices: execute his assignment or abandon it. The latter option would constitute desertion.

Since he did not choose desertion, he had to follow the order to its logical conclusion.

That some civilian commentators ignore this reality is perhaps symptomatic of our national culture, where we assume rules are endlessly negotiable. Military institutions do not run on that logic. If there was any impropriety in the deployment, the responsibility lies squarely with those who issued the order, not with the officer who executed it. Interestingly, the military hierarchy and the supervising ministry have not denied issuing the directive.

That fact alone should end the speculation about the officer’s culpability. It is against this backdrop that I earlier described Yerima as professional. Many disagree because they evaluate his restraint through the lens of civilian conduct. But reflect on what happened: a uniformed officer was publicly insulted, called a “fool,” threatened, and physically approached in an aggressive manner by a powerful political figure. In a highly volatile military-civilian interface, such moments often escalate into bloodshed.

Soldiers are trained to interpret perceived threats against their superior officers, or against themselves, as triggers for defensive action. One sudden movement, one mistaken assumption, one panicked reaction could have resulted in an irreversible tragedy. For those familiar with the endurance threshold of human beings, especially among some culturally sensitive groups, the insult “fool” is not a simple word. It is defamatory.

The officer had grounds to sue for defamation if he so wished. The fact that he did not retaliate physically or verbally is, in my view, a testament to discipline. What many Nigerians fail to appreciate is the razor-thin line that separates order from chaos when civilians directly confront armed personnel. A single ill-timed gesture could have produced headlines none of us wishes to imagine. The officer’s restraint prevented such a disaster. Still, some commentators hold onto a principle that I also support: the military must never overshadow the rule of law.

On this point, we have no disagreement. But the issue at hand must be carefully distinguished from the widespread abuse where military personnel are deployed to guard a private property. That phenomenon is condemnable and unconstitutional.

Yet the law recognizes a narrow exception: former military and paramilitary chiefs, by virtue of their previous responsibilities and security implications, remain entitled to limited military protection even after retirement. The logic is simple. These are individuals who, in the course of duty, made decisions of national security consequence. Leaving them completely exposed after office, without protection for themselves, their families, and sometimes their properties, may pose national risks. The same reasoning explains why former Presidents continue to enjoy security protection for life and assets.

Whether one agrees with the fairness or cost of this arrangement is another debate entirely. But it is the prevailing legal framework. However, when the matter is purely a land title dispute, the courts offer the proper route. If the former service chief indeed lacks a valid title, the FCT Administration must file an action. Likewise, the military personality affected may also choose litigation, except that in this particular case, the officer’s superior is already in physical possession, which complicates matters as possession is 9/10th of the law.

Once a court issues judgment, enforcement lies not with ministers or soldiers but with the bailiffs of the judiciary. If the military obstructs lawful enforcement, contempt proceedings must follow. That is the way of constitutional order. But to pretend that this is what ordinarily happens in Nigeria is to be wilfully blind. Reality tells a harsher story. I speak from direct experience. My client secured judgment up to the Court of Appeal concerning a piece of land near Signals Barracks in Apapa, Lagos which was hijacked by the Nigerian Army. Twice the Ministry of Defence and the Nigerian Army formally handed over the land. And yet, for nearly twenty years, soldiers have physically prevented entry, turning legal victory into a pyrrhic achievement.

That is the tragedy we must confront, not the obedience of an officer who followed a (legitimate) order in a political flashpoint. The deeper problem is our prolonged domestication of the military within civilian urban spaces. Military culture is fundamentally different from civilian culture. Soldiers are trained in warfare, not in community relations. Their worldview is one of threat, response, and survival. Civilians operate on dialogue, negotiation, and persuasion. These two systems rarely mix smoothly.

The late Fela Anikulapo-Kuti captured this dichotomy in the famous song “Zombie,” not as an insult but as a sociological commentary on the rigid obedience that defines military life. When we keep men trained for combat within densely populated civilian areas and subject them to civilian provocations, misunderstandings are inevitable. If we insist on retaining soldiers within cities, then we must accept the consequences. Alternatively, we may attempt to demilitarize or “civilianize” them, but doing so risks weakening our defence capability.

On the other hand, modernizing the military and redefining its roles may overstretch national resources. We are caught in a policy paradox. Nevertheless, solutions exist. Nigeria must begin relocating military formations to the outskirts of cities, as is standard practice globally. Many barracks today are sitting in the heart of urban centres because civilian development has expanded around them.

These facilities must be moved. Doing so will improve military readiness, reduce friction, and enhance national security, particularly in combating terrorism, kidnapping, and banditry.

Alongside relocation, we must review the privileges and entitlements of military personnel, both serving and retired, in a pragmatic way. Do we continue to extend these benefits indefinitely? Under what circumstances? At what cost? These are conversations Nigeria must confront honestly. Until we restructure the military’s physical location, legal framework, and institutional relationship with civilian authority, confrontations like the Wike-Yerima encounter will continue to erupt. Now, let me return briefly to the officer’s much-discussed remark: “I am not a fool; I have integrity” which has become a refrain in Nigerian general discourses to the extent that the always celebratory Kegite Club has turned it into a song.

That statement, in context, is loaded. Integrity is the most valuable asset any human being can possess. When an officer under public attack asserts his integrity, he is making a moral declaration. Implicitly, he is drawing a line, defending his honour and perhaps suggesting, however subtly, that the aggressor’s conduct fell short of the same virtue. In a society where public office is often divorced from public ethics, Yerima’s statement should provoke introspection. How many public officials today can confidently assert that they have integrity, not in words but in conduct? How many wield authority with humility, fairness, and restraint? How many treat ordinary citizens or even officers in uniform with dignity and vice versa? Sometimes the smallest moment reveals the deepest truths about a nation.

As we debate this matter, we must resist the temptation to focus on the wrong actor. Yerima is not the villain. He is a symptom. The real issues are structural: the militarization of civilian spaces, the politicization of land administration, the fragility of public institutions, the lack of clarity in civil-military relations, and the absence of consistent rule-of-law enforcement. These challenges will not vanish through moral outrage or social media commentary. They require careful institutional reforms, courageous leadership, and a sober national conversation about the boundaries of power. Nigeria must decide:

Do we want soldiers to be soldiers? Do we want the rule of law to be supreme?

Do we want institutions strong enough to manage both without unnecessary frictions? Until we answer these questions honestly and implement reforms accordingly, we will continue to witness scenes that embarrass the nation and undermine its democratic claims. Ultimately, the lesson from this episode is simple: integrity, though intangible, is powerful. Some possess it quietly. Others proclaim it loudly only when challenged.

And some, by their conduct, show that they may have misplaced theirs along the way. What remains constant is that integrity, like truth, cannot be concealed. It reveals itself in moments of pressure. And in that moment on that contentious piece of Abuja land, it was Naval Lieutenant Commander Yerima, not the political figure confronting him, who demonstrated it.