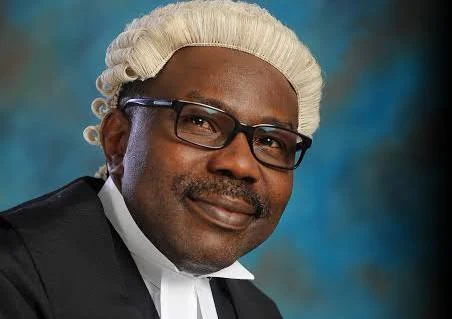

The need for air interconnectivity across Africa – Dr. Muiz Banire

The dream of a truly interconnected Africa has long animated the imagination of statesmen, economists, and integrationists across the continent. From the days of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) to the present African Union (AU), the rhetoric of “African unity” has often found expression in political communiqués, trade pacts, and borderless aspirations. Yet, one of the most visible indicators of our disjointed reality lies not in the texts of our treaties but in the skies above us, in the fragmented, inefficient, and costly state of air travel across Africa.

It is easier, today, for a traveller to fly from Lagos to Paris and connect to Dakar than to fly directly between those two African capitals. A flight from Nairobi to Accra often requires a European layover. A journey from Nairobi to Dakar may require a layover in Paris or Istanbul, a curious absurdity on a continent that loudly proclaims Pan-Africanism and economic integration. For all our talk about “Africa Rising,” the skies above us remain a patchwork of disconnected routes, bureaucratic hurdles, and policy inertia. The sheer irony of this phenomenon is profound: in an age of globalization, where connectivity defines competitiveness, Africa remains disjointed in its own aerial space. In the same vein, ideas and commerce thrive only when there are channels of movement. Yet Africa, for all her youthful energy and market potentials, continues to choke under her own disconnection. The inefficiency of African air interconnectivity is not merely a technical problem, it is a historical inheritance and a policy failure. By this, I mean that the continent’s dysconnectivity is not accidental but by design.

The roots of this problem are not hard to trace. The colonial transport architecture was designed to link African territories to their European metropoles, not to each other. Hence, the air routes, ports, and rail lines were radially structured, outward to Europe rather than horizontally within Africa.

Decades after independence, many African nations retained this infrastructural logic, while bilateral protectionism among national carriers further entrenched fragmentation. The logic of the colonial economy was extraction, not integration.

Decades after independence, many of our countries inherited these aerial routes and, tragically, the mindset that came with them. National carriers became symbols of sovereignty rather than instruments of efficiency. The result has been a continent where intra-African air travel remains among the most expensive in the world. According to the African Airlines Association (AFRAA), only about 20% of air traffic in Africa is intra-African. High ticket costs, poor scheduling, cumbersome visa requirements, and inadequate airport infrastructure collectively discourage both business and leisure travels. For a continent aspiring to achieve a continental free trade area (AfCFTA), the largest in the world by membership, such disconnection is an economic contradiction. A businessperson flying from Kigali to Lagos often pays more than someone flying from Lagos to Dubai. The absence of seamless air links does not just inconvenience travellers; it suffocates trade, tourism, and investment, the very oxygen that modern economies breathe. Efficient air interconnectivity is not a luxury; it is an economic necessity. It is not a luxury reserved for the rich; it is a developmental necessity. Air travel is the bloodstream of regional integration.

Modern economies are built on the speed of movement of people, goods, and ideas. Air transport enables regional value chains, tourism, and professional mobility. For Africa, where many national economies are small and landlocked, aviation can bridge distances that roads and railways cannot feasibly cover in the short term. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) aims to create a single market of over 1.3 billion people. But trade agreements cannot move goods; logistics do. You cannot build value chains when your traders, professionals, and investors cannot move freely and affordably. A conference of African innovators should not find it cheaper to meet in Dubai than in Addis Ababa.

The absurdity speaks for itself. A trader in Kigali must be able to reach his partner in Accra efficiently; a business meeting between Cairo and Cape Town should not demand a European detour. Without seamless air links, AfCFTA risks being a paper tiger. Moreover, the tourism potential of Africa, from Zanzibar to the Serengeti, from the Pyramids to the Cape, remains underexploited largely due to the difficulty of inter-African travel. From the Pyramids of Giza to the dunes of Namibia, from Zanzibar’s turquoise shores to Cape Town’s vineyards, Africa holds treasures that could sustain millions of livelihoods. Yet many Africans have never visited another African country. The hurdles are too high, ticket costs, poor scheduling, restrictive visas, and outdated airports. A regional tourist circuit connecting these destinations could generate millions of jobs and billions of dollars in revenue if air travels were simplified and affordable. Until we dismantle these barriers, we cannot truly speak of one Africa. To be honest, Africa has not been silent on this matter. As far back as 1988, African leaders recognized this gap and attempted to correct it through the Yamoussoukro Declaration on the liberalization of access to air transport markets in Africa.

It sought to create a unified African airspace by removing restrictions on routes, capacity, and ownership. In 1999, the initiative was formalized into the Yamoussoukro Decision (YD), and later, in 2018, revived under the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM) , one of the AU’s flagship Agenda 2063 projects. The dream was simple: open skies, shared prosperity. But like many African dreams, it has struggled to take flight. Only a fraction of our nations have implemented the Yamoussoukro framework. Protectionism, fear of competition, regulatory inconsistencies and the ghost of failed national carriers continue to haunt our progress. Many governments still see aviation as a prestige project rather than a business catalyst. In many cases, political will has faltered in the face of short-term economic insecurities. The result is a sky cluttered with red tape and grounded ambition. Africa must move beyond rhetoric. Thus, the promise continues to be paralyzed. Liberalization of airspace, harmonized regulations, and credible enforcement mechanisms are non-negotiable if we are to turn policy into progress. Africa must persist in the journey toward full air liberalization, not because it is easy, but because it is essential to its integration.

An efficient African air network requires both visionary policy and pragmatic business models. The collapse of many national airlines like Nigeria Airways, Ghana Airways, Air Afrique, and Zambia Airways, among others, reflects the unsustainability of politically driven carriers. This collapse of several once-proud African airlines stands as a cautionary tale. Most were sunk by inefficiency, over-politicization, and bureaucratic meddling. The way forward is not to resurrect them as symbols of nostalgia but to build partnerships rooted in efficiency and scale. The future lies in regional consolidation and hub-based cooperation. Ethiopian Airlines has demonstrated that an African carrier can compete globally through sound management and strategic partnerships. Its “hub and spoke” model in Addis Ababa connects over 60 African destinations efficiently. Similar regional hubs, in Lagos for West Africa, Nairobi for East Africa, Johannesburg for the South, and Cairo for the North, could form the backbone of a continental air grid, with smaller carriers feeding into them. Governments should focus on providing enabling infrastructure, while private capital and expertise drive operations. The business of flying must be left to those who understand the business of flight.

Governments must therefore prioritize open skies, harmonized regulations, safety standards, and public-private partnerships to sustain operations. The private sector, not the state, must drive the revival of African aviation, with governments creating the enabling environment through infrastructure, bilateral air service agreements (BASAs), and predictable policies. Beyond policy, Africa needs infrastructure that reflects her aspirations. Too many of our airports remain relics of the 1970s, cramped terminals, epileptic power, and manual check-ins. Many remain relics of a bygone era, under-equipped, under-staffed, and inefficiently managed. We must modernize with purpose: safe runways, digital systems, e-visa integration, and efficient ground transport links between airports and city centers.

Our airports should no longer be treated as mere travel depots but as economic ecosystems, hubs of logistics, trade, and technology. Equally, our regulatory agencies must be independent, professional, and aligned across borders. The dream of low-cost intra-African airlines like the the Ryanair or FlyDubai of Africa, will only become reality when taxes, fees, and bureaucratic costs are harmonized and reduced. Investment should focus on airport safety, maintenance, and passenger experience.

At its deepest level, air interconnectivity represents something larger than aviation. It is about the freedom to move, the courage to trust, and the will to cooperate. It is the visible architecture of an invisible unity, the embodiment of Pan-Africanism in motion. Efficient air interconnectivity is a metaphor for Africa’s broader integration struggle. It represents how the continent must transcend colonial borders, bureaucratic inertia, and national egoism to build shared prosperity. A continent that cannot fly freely within itself cannot trade freely, think freely, or grow cohesively. As long as Africans find it easier to connect through Europe or the Middle East than through their own capitals, the project of continental integration remains unfinished.

The skies over Africa are not the property of any single nation; they are the arteries of a shared destiny. If harnessed, they can carry the lifeblood of commerce, culture, and cooperation across the continent. The time has come to clear our skies of fragmentation. Our economic emancipation cannot be complete if our journeys remain circuitous. This vision therefore surpasses runways. The dream must not be simply open skies but real air connectivity. Doing this is no rocket science if only African leaders are visionary. Nothing esoteric in floating a viable African airline that interconnects the continent, particularly through the vehicle of the African development bank, possibly in conjunction with the African import and export bank.

Since we have identified the challenge of the sovereign airlines to be inefficiency, over-politicization, and bureaucratic meddling, saddling these professional institutions with the responsibility of floating and managing the airline will eliminate the challenges and appropriately position it on the path of viability, efficiency and success. This much African leaders must urgently wake up to fix in order to ensure African air connectivity. Hence, establishing efficient air interconnectivity across Africa is not merely about transport policy, it is about economic transformation, continental unity, and dignity in mobility. Efficient air interconnectivity is not just about movement; it is about meaning.

It is about reclaiming our space in the modern world, connecting our people to each other, and ensuring that the winds beneath our wings carry the promise of a continent finally learning to soar together. After all, the eagle does not fly because the wind is gentle, it flies because it was born to rise. The challenge is formidable, but so too is the opportunity. The continent that once supplied the world with the wind beneath others’ wings must now learn to soar on its own.