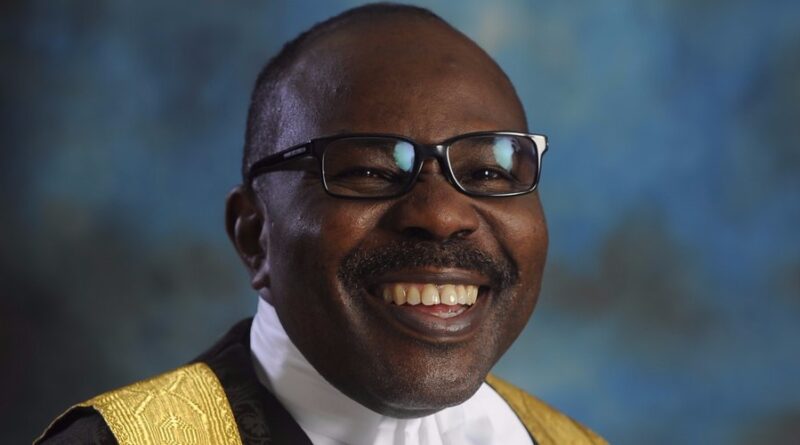

The test of institutional maturity in party congresses: The APC story Dr. Muiz Banire

For the ruling party leaders, as the All Progressives Congress commences another round of its congresses across the federation, a moment that ordinarily ought to be routine administrative housekeeping has once again assumed the character of a defining national conversation. Party congresses, in any serious political system, are not mere ceremonial gatherings designed to recycle familiar faces or reward loyalists with titles; they are the oxygen chambers of democratic institutions, the arenas where renewal either happens or stagnation is entrenched. In a polity such as Nigeria, where political parties often oscillate between vibrancy and vulnerability depending on electoral cycles, such congresses must be treated not as rituals of affirmation but as laboratories of institutional rebirth.

The health of a political party is measured less by the volume of its victory songs and more by the strength of its internal organs. A party that wins elections yet fails to renew its structure is like a house painted freshly on the outside while termites feast within the beams. For any ruling party especially, the temptation is always strong to assume that incumbency reward is a substitute for internal democracy. History, however, is unkind to such illusions. Across continents and political traditions, dominant parties have crumbled not because opposition forces were too strong, but because complacency hollowed them from within. The lesson is clear: victory is not permanence; relevance must be renewed. The ruling party in recent past boasts of intimidating number of new members from the opposition parties. As this occurs, the least that can happen is to seize the opportunity of the congress and conventions to integrate these new members into the party structure.

Except this is properly manicured, it could be the greatest undoing of the political party. It is therefore incumbent that the process be allowed to be substantially transparent even where consensus is adopted. Give and take must be central to the engagement.

It is against this backdrop that the present moment calls for courage, foresight, and sincerity on the part of party leaders and stakeholders. Injecting new blood into party structures is not a fashionable slogan; it is an existential necessity. Renewal does not imply the abandonment of experience, nor does it require the humiliation of elders whose sacrifices built the platform. Rather, it demands a deliberate intergenerational handshake in which institutional memory meets fresh energy. Without such synthesis, a party risks becoming either a museum of veterans or a laboratory of inexperienced enthusiasts. The task, therefore, is balance: continuity without rigidity, change without recklessness.

One of the most troubling features of party politics in our environment has been the phenomenon of structural wobbling in key states. These are the strategic strongholds where internal crises, factional rivalries, and leadership tussles repeatedly weaken organisational coherence. This was the undoing of the party chapter in the last general election in which the party had to struggle to win the gubernatorial election in Lagos State while losing the presidential election. When state chapters of a ruling party become theatres of endless disputes, the damage extends far beyond party headquarters. Governance itself suffers, because energy that ought to be invested in public service is diverted into conflict management. I am a living testimony to this as I have been recently saddled with an assignment of this nature, and in a position to attest to the valuable time and resources gradually consumed.

Citizens then begin to question whether the party in power can effectively manage a nation when it struggles to manage its own internal affairs. This is a word of caution. Institutionalising stability at the state level must therefore be treated as a cardinal objective of these congresses.

This requires transparent procedures, as earlier opined, credible delegate selection, fair dispute-resolution mechanisms, and the political will to enforce rules irrespective of personalities involved. The culture of impunity within party structures, where influential figures bend procedures to suit private ambitions, is the fastest route to organisational decay. A party that tolerates injustice internally cannot convincingly preach justice nationally. Discipline, after all, is not an abstract virtue; it is a daily practice that must begin at home.

The party must therefore be courageous enough to uphold the rule of law and the party constitution at all times. Equally important is the question of ideological clarity. Many parties in emerging democracies suffer from what may be described as philosophical anemia.

They possess names, symbols, and slogans, yet lack clearly articulated ideological direction. Congresses should therefore serve not only as leadership selection platforms but also as policy conventions where members debate ideas, refine principles, and reaffirm collective purpose. When members understand what their party stands for beyond elections, loyalty becomes deeper and defections become rarer. Ideology, in this sense, is the glue that binds ambition to purpose. It is however unfortunate that in our clan, this matters not. All that is to party congresses is selection and imposition of party operatives. The party need urgently to imbibe this culture and encourage it even at the ward and local government levels much less at the State level. It must not be left to the National Convention alone. Youth inclusion must also move from rhetoric to reality.

A party that excludes its younger generation is effectively writing its own retirement letter. The demographic reality of our nation is unmistakable: the majority of citizens are young, energetic, digitally savvy, and increasingly politically conscious. To keep them at the margins of party structures is to deny the party access to the very constituency that will determine its future. But youth inclusion must not be tokenistic. It must involve real responsibilities, measurable roles, and genuine participation in decision-making processes. When young members are trusted with leadership, they develop ownership; when they are sidelined, they develop resentment.

This explains the current challenge of the ruling party relative to the Labour Party. Thus, this is an opportunity to remedy this situation. Women’s participation is another indispensable pillar of renewal. No political institution can claim maturity while half of society remains under-represented within its ranks. The measure of progress is not the number of women who attend congresses but the number who emerge from them as leaders. The affirmative action must start with the political parties, particularly the ruling party. It is when this is actualized in the political structure that it becomes easier to integrate same into the governance structure. Inclusion must therefore be intentional, structured, and protected by enforceable rules rather than dependent on goodwill. Societies advance fastest when leadership reflects their diversity.

Furthermore, the credibility of any congress rests heavily on the integrity of its process. Transparency is not merely desirable; it is indispensable. Clear guidelines, open accreditation, impartial supervision, and prompt resolution of disputes create confidence among members. Conversely, opaque procedures breed suspicion, and suspicion is the seed from which factional crises grow. Technology, if properly deployed, can assist greatly in this regard through digital membership registers, transparent voting systems, and real-time monitoring. This again will constitute the forerunner to the conduct of the general elections in the country. Modern political parties must embrace modern administrative tools if they hope to command modern legitimacy. There is also a broader national implication to these internal exercises. Political parties are not private clubs; they are public institutions in democratic clothing.

Their internal culture ultimately shapes national governance culture. When parties practise consultation, fairness, and accountability internally, they are more likely to replicate those virtues in government. When they practise exclusion, arbitrariness, and patronage internally, the same habits inevitably spill into public administration. Thus, the stakes of party congresses extend far beyond party offices; they touch the very architecture of national development. It is therefore imperative for party leaders to approach this season not as a contest of supremacy but as a covenant of stewardship. Leadership positions within party structures should not be seen as trophies but as trusts.

The true test of a political organisation is not how loudly its members proclaim loyalty, but how faithfully its leaders protect its institutions. Structures outlive individuals, and wise politicians invest more in institutions than in personal influence. The party must avoid the pitfall of building strong individuals as opposed to strong institutions. A wise man is the one that knows the limit of his strength while a strong man is the one that knows the limit of his wisdom. Those who build structures build legacies; those who build factions build footnotes.

Let the elders be more accommodating of the upcoming political youth. In the final analysis, the ongoing congresses present a rare opportunity, an opportunity to reset, to reconcile, to rejuvenate, and to reaffirm. They can either become milestones of institutional consolidation or mere milestones of routine ceremony.

The choice rests squarely in the hands of those entrusted with leadership today. Posterity will not judge them by how many offices they occupied, but by how strong they left the structures they inherited. Renewal is not automatic; it is intentional. And for any party that truly desires to institutionalise a vibrant political structure capable of withstanding the tempests of time, the injection of new blood is not optional. It is destiny’s demand.