Cynicism And The ‘Impregnable Wall’: Can Nigerians Rescue 2027?

After every election in Nigeria—especially the contentious ones—a familiar chorus rises: “They will rig it.” “Nothing will change.” Following the recent off-cycle governorship polls, this chorus has grown louder. On the streets, in offices, and across social media, many Nigerians have already written off the 2027 general elections as a lost cause. The potential impact of the 2027 general elections on Nigeria’s future is straightforward and devastating: the system is irredeemably rigged and talk of reform is futile.

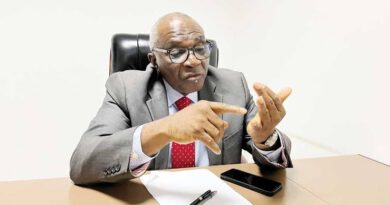

In a recent keynote address titled “Making Our Votes Count: Action, the Antidote to Cynicism,” Dr Sam Amadi, Director of the Abuja School of Social and Political Thought, pinpointed the real threat this attitude poses. “The gravest threat to free and fair elections in Nigeria in 2027,” he argued, “is not a corrupt INEC, nor a compromised judiciary, nor partisan security agencies. The true threat is our belief that nothing can change—a crippling hopelessness that breeds either inaction or reactive efforts that accomplish very little.” The need for action to combat this cynicism is urgent.

This cynicism is rooted in historical trends. It sits atop what many perceive as an impregnable wall blocking meaningful electoral reform. At the heart of this wall is a National Assembly that has repeatedly shown little appetite for reforms that reduce incumbents’ advantages or improve electoral outcomes. “The Presidency under President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has thus far given no clear indication that electoral reform is a priority. Unlike former Presidents Jonathan and Buhari, who at least submitted amendment bills or established review committees, this administration has done nothing about electoral reform,” Dr Amadi bluntly noted. Instead, it has “worsened the environment of electoral integrity by making partisan appointments into the electoral management body.”

These pillars are surrounded by other blocks: opposition parties too weak or disorganised to provide sustained oversight or viable alternatives; a judiciary that often usurps the role of voters while upholding questionable polls; INEC operatives benefiting from the status quo; and a civil society and electorate oscillating between outrage and resignation. Together, these elements form a wall convincing many Nigerians that profound change before 2027 is impossible.

To grasp why cynicism has spread so profoundly, we must confront an uncomfortable truth: elections in Nigeria have, for much of our history, been manipulated, Dr Amadi asserted. Free and fair polls have often been the exception, not the rule. Even the two elections commonly hailed as credible—June 12, 1993, and 2015—were flawed. They are remembered positively mainly because their outcomes aligned with public expectations or resulted in incumbent defeats. Election observer reports show that the 2015 election, for example, suffered serious irregularities, especially where electronic card readers failed and “bogus results” were declared.

This is not just a Nigerian phenomenon; it is an African one. Many post-colonial states were founded on fragile, exclusionary institutions and unequal political economies. In such contexts, political office is not just service; it is often the primary path to wealth, status, and security. As Amadi notes, the “economic and social benefits of winning an election and the enormous costs of losing it” raise the stakes so high that elections easily become battles. Where politics is war, “all is fair,” and rigging becomes rational. Paul Collier warned that when elections are criminalised, “only criminals will be involved.” That harsh reality continues to haunt many African democracies.

It is no surprise, then, that increasing numbers of young Africans are disillusioned with democracy itself. Many, having not lived through past military brutality, romanticise recent coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, or Niger as quick fixes to civilian failures. Even respected elders like former President Olusegun Obasanjo have publicly questioned whether liberal democracy suits African realities. In this climate, one might ask: Why should a Nigerian in 2025 care about free and fair elections in 2027?

The answer lies in what elections achieve when they function reasonably well. Beyond ideals and slogans, credible elections serve two crucial purposes. First, they create incentives for leaders to listen. Presidents, governors, and legislators who know they can be “easily voted out” have stronger reasons to respond to public concerns. This doesn’t guarantee good governance, but without this pressure, accountability becomes nearly impossible.

Second—and perhaps more vital in Nigeria’s context—is that elections serve as a conflict-management mechanism. Political theorist Adam Przeworski argues that elections aren’t perfect decision-making tools; they are frameworks allowing people with different views to “struggle peacefully” over governance. In Nigeria’s deeply pluralistic society— marked by ethnic, religious, and regional divisions—this minimal function is crucial. When elections are seen as hopelessly rigged, political actors resort to violence, secessionist rhetoric, or military intervention as the only paths to power.

If the stakes are this high, why are Nigerians sinking into cynicism rather than action? One reason lies in how the current administration has handled the electoral question. As Amadi notes, President Tinubu has neither spoken convincingly on electoral reform nor taken visible steps toward it. Public perception is made worse by partisan appointments: “For the first time in a long while,” nearly everyone involved in election management— from INEC to security agencies and the judiciary—appears tied to the President by ethnicity or political alliance. The mood is summed up in a familiar refrain: “Tinubu is not Jonathan… Tinubu is not a gentleman, oo. Tinubu is Jagaban.”

Yet cynicism presents only a partial picture. It downplays pockets of progress and the power that organised citizens still wield. Nigeria’s elections are not universally worse. Logistically and technologically, genuine improvements have emerged: fewer complaints about late materials, fewer incidents of premature results declaration, and electronic accreditation has limited turnout inflation. These are signs that change is possible, and hope should not be lost.

The challenge is that the system adapts. New technologies have spawned new forms of manipulation. During the 2023 presidential election, INEC allegedly circulated the wrong passwords, making it impossible to upload results electronically. Result sheets were tampered with, and trust was broken. In the Edo governorship poll, opposition voices accuse INEC of declaring outright “fake results.” Technology strengthened parts of the process but did not eliminate human agency or political pressure. However, with collective action, we can counter these manipulations and ensure a fair electoral process.

This makes the recent appointment of Prof. Joash Amupitan as INEC Chairman all the more significant. Former National Human Rights Commission chair Prof. Chidi Odinkalu describes Amupitan as “a person of basic decency and integrity” who would not preside over multiple conflicting results. However, Odinkalu warns that integrity alone may not suffice. INEC operates in a complex bureaucracy where “no senior politician—from the presidency to state governors—does not have a plant.”

Amupitan faces the test of navigating these “multiple principalities.” Upcoming governorship elections in Ekiti and Osun will serve as “electoral laboratories” to observe his approach and how citizens, parties, and the judiciary respond. Nigerians are watching.

But watching alone is not enough. If rigging is a “manufactured outcome,” then it can be countered by deliberate, strategic action. Amadi calls for an “election integrity defense system” with four pillars: INEC, political parties, civil society, and the judiciary.

At INEC, the focus must be on institutional integrity—developing and enforcing clear rules, ensuring meaningful participation by parties and observers, pursuing legal action against irregularities, and supporting reformist staff who resist political interference.

For political parties, especially opposition ones, the challenge is to reclaim vigilance rather than outsource it to NGOs. Parties are the primary beneficiaries of credible elections, yet often neglect mandate protection, fail to train polling agents, and replicate bad practices internally. They must build internal democracy and external oversight to champion voters’ rights genuinely.

The judiciary sits at a dangerous crossroads. Courts now decide election outcomes but often impose impossible evidentiary burdens while INEC withholds essential documents. Lawyers, the media, professional bodies, and citizens must demand reforms to electoral adjudication procedures and hold judges morally accountable for decisions that undermine popular will.

None of this is easy. It is simpler to laugh bitterly on election day and stay home than to join a party, serve as an agent, support litigation, or engage in detailed discussions about electoral reforms. Cynicism is the cheaper, short-term option, but it’s far more dangerous. It hands victory to those who profit from rigging, without requiring any effort on their part.

The 2027 election will be decided not only at polling units but by what Nigerians do—or fail to do—between now and then. Will the country continue repeating that nothing can change? Or will Nigerians act as though their votes and their future still matter?

*Dr Dakuku Peterside is the author of Leading in a Storm and Beneath the Surface